The Beginnings of Space Medicine Research

Competition to develop rockets, mainly between Russia (the former Soviet Union) and the USA, began around the late 1940s after the end of World War II. Research on aerospace medicine, the foundation required to realize human spaceflight, began in the 1950s.

Experiments on high-altitude flights were carried out using balloons and airplanes, and systems for environment control and life support mechanisms were developed.

On April 12, 1961, the first human spaceflight was achieved with the flight of Yuri Gagarin, a former Soviet Union cosmonaut. Prior to launch, some claimed that long exposure to a microgravity environment would be fatal, but Gagarin's flight—humanity's first human orbit of the earth, taking approximately 108 minutes—put those worries to rest.

NASA's Gemini Program was undertaken with the intent to extend the number of days of human flight, and many medical measurements were taken during the Gemini and Apollo Programs.

Development of Space Medicine

During NASA's Skylab Program in 1973 and 1974, three human flights are launched, and each time, three astronauts traveled to orbit. During these missions, experiments were carried out to investigate specific effects on the human body, and this led to a more systematic understanding of the medical issues involved in spaceflight.

In 1981, NASA successfully flew the Space Shuttle for the first time. The Space Shuttle enabled transport of research equipment into space and allowed seven astronauts to stay in space for two weeks.

The Space Shuttle Program enables to take full-fledged equipment for medical experiments into space.

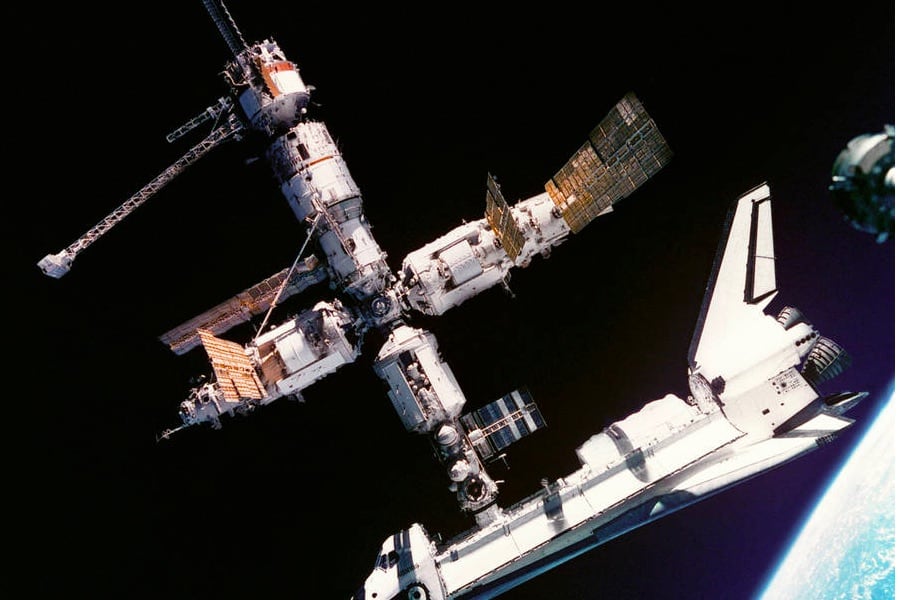

Meanwhile, with the aim of establishing technology for long-term presence in space, Russia launched a total of nine modules into orbit over 11 years from 1986, and constructed the Mir space station for extended stays by cosmonauts.

In 1995, Russian cosmonaut Valeri Polyakov, boarding Mir for 438 days, set the record for the longest stay in space on a single flight. Another Russian cosmonaut, Gennady Padalka, has the record stay in space for 879 days over the course of five flights.

Thus, it was found that humans can live in space for one year or more, but the space environment affects individuals differently, and not everyone can safely stay in space for long periods.

Space medicine began with the question of whether or not humans can survive in space. Today, the focus is on improving methods of managing astronaut health.

The Beginnings of Japan's Space Medicine Operations

At the time the former Soviet Union and the USA were competing in space development, Japan was just starting to enjoy its post-war period of high economic growth.

When NASA's Space Shuttle flights commenced in 1981, Japan began to consider participating in space experiments.

Japan's medical operations, including the health management of astronauts, date back to Japan's first astronaut recruitment and selection tests between 1983 and 1985.

Prior to the selection of Japan’s first astronauts, JAXA (at that time known as NASDA) first examined medical testing and evaluation methods based on NASA's medical standards for astronauts. Actual medical selection of Japanese astronauts began in 1983, and three astronauts—MOHRI Mamoru, MUKAI Chiaki, and DOI Takao—were selected in 1985. At this time, a dedicated flight surgeon was recruited to manage the health of Japanese astronauts.

In selection of the next Japanese astronaut, WAKATA Koichi, NASA’s medical standards for mission specialists were applied. Along with the initial screening of application documents, a simple medical examination—measuring blood pressure, height, eyesight and other such criteria—was carried out. During the first test, a written psychological screening was conducted. During the second test, candidates were admitted to a university hospital for five days and subjected to intensive medical and psychological testing from early in the morning to late at night. The six candidates who advanced to the third test underwent medical testing at the Tsukuba Space Center and NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

The 1995 astronaut selection test, where NOGUCHI Soichi was selected, and the 1998 astronaut selection test, where HOSHIDE Akihiko, YAMAZAKI Naoko, and FURUKAWA Satoshi were selected, were primarily conducted at the Tsukuba Space Center.

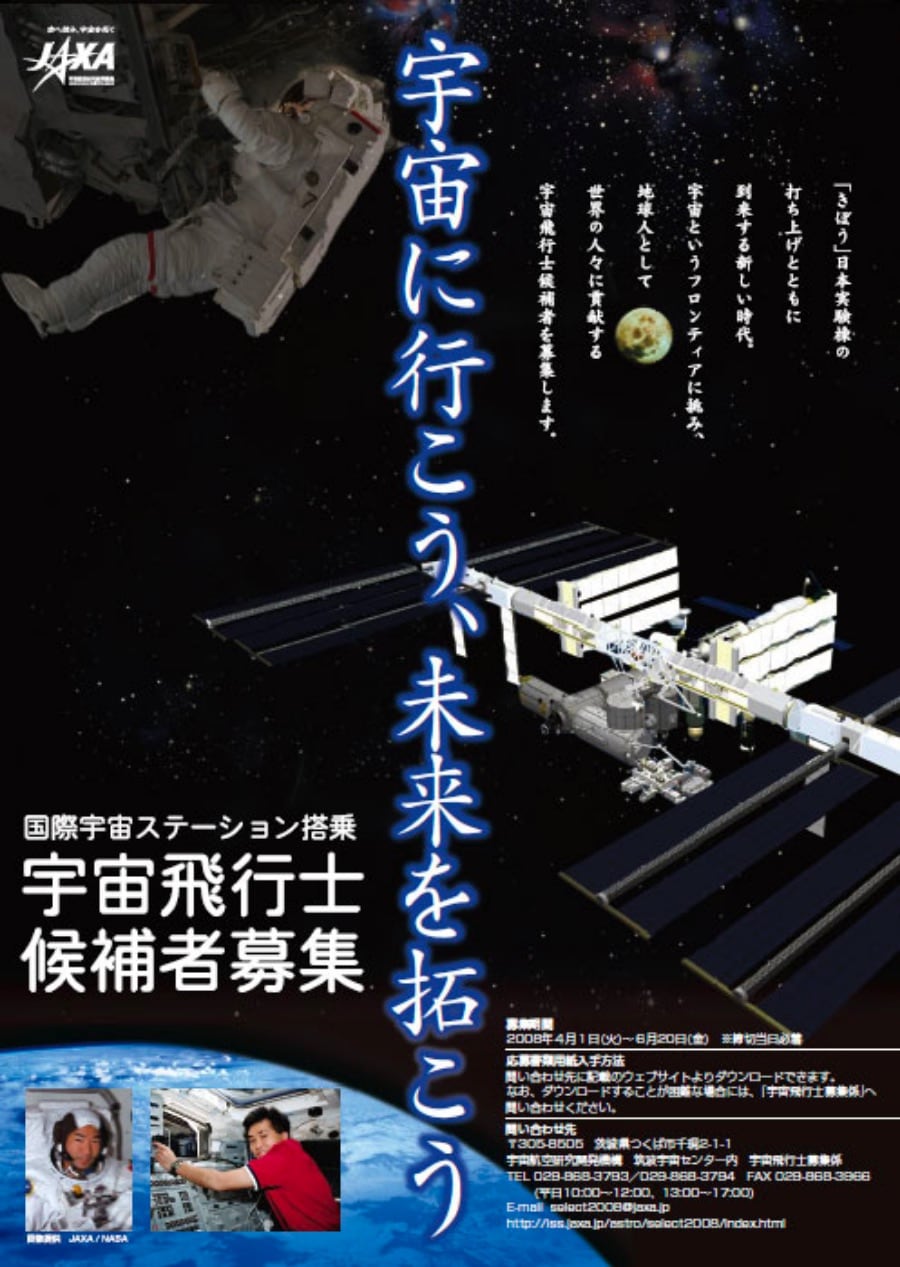

For the recruitment of Japanese astronaut candidates who can fly long duration missions to the International Space Station (ISS) in 2008, where YUI Kimiya, ONISHI Takuya, and KANAI Norishige were selected, ISS International Medical standards were applied, which contributed to improve the efficiency of medical screening.

Japan's Participation in International Joint Research

Japan has participated in a number of international joint experiments, including a closed-environment experiment in Russia, and a long-term bed rest experiment in France. In the long-term bed rest experiment, carried out jointly with France’s National Centre for Space Studies (Centre national d'études spatiales, CNES) in 2001 and 2002, the hypothesis that bisphosphonates (a class of drugs used to treat osteoporosis) may be effective for preventing loss of bone mass and urinary tract stones during protracted bed rest was examined. The experiment confirmed the drugs' effectiveness.

Subsequent joint research was conducted by the USA and Japan to verify the hypothesis that these bisphosphonates would demonstrate the same efficacy for humans enduring long stays in space.

In future human exploration of the moon, and perhaps even the eventual human exploration of Mars, humans need to stay in space for even longer periods. To maintain the health of astronauts and enable them to successfully accomplish their missions, the various effects of space on the human body are being investigated, and space medicine research is working to develop countermeasures to them.

Unless specified otherwise, rights to all images belong to ©JAXA