Interview

04

Interview01.

Artificial Blood achieved through 20 years of passionate research

Interview02.

Getting to the bottom of human's greatest infection periodontal disease

Interview03.

True sustainable society proposed by a biomass researcher

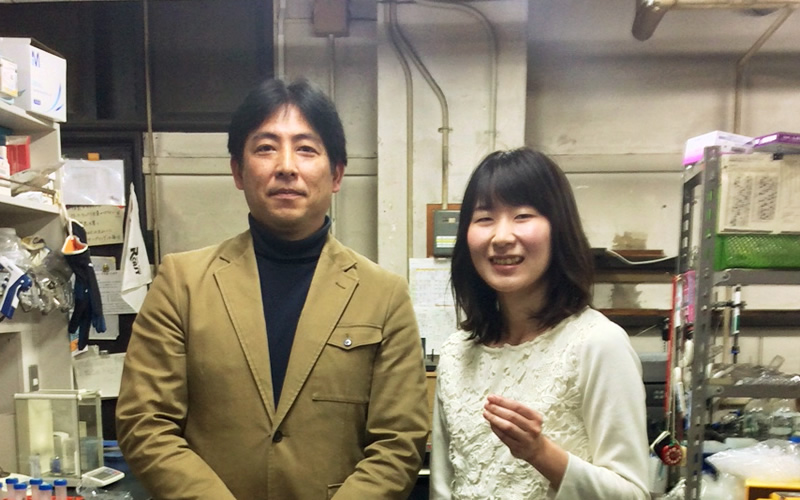

Kiyohiko Igarashi

Associate Professor, Faculty and Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, the University of Tokyo

Born in 1971 in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan.

1994: Graduated from the Department of Forest Products, Faculty of Agriculture, The University of Tokyo, Japan.

1994: Master's degree program at the Department of Forest Products, Graduate School of Agriculture, The University of Tokyo.

1996: Doctoral degree program at the Department of Biomaterial Sciences, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo.

Researcher, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Georgia, USA.

1998: Research Fellowship for Young Scientists (DC), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

1999: Research Fellowships for Young Scientists (PD), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

Postdoctoral Fellowships, Biomedical Centre, Uppsala University, Sweden.

2002: Assistant Professor, Department of Biomaterial Sciences, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo.

2007: Assistant Professor, Department of Biomaterial Sciences, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo.

2009: Associate Professor, Department of Biomaterial Sciences, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo (current position).

2016: Visiting Professor, VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland Ltd., Finland.

The third interview is with Dr. Kiyohiko Igarashi, Associate Professor at the Faculty and Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, the University of Tokyo, who is well known for his research on the cellulase enzymes that degrade cellulose, the largest unused biomass on the earth. The interview ranges broadly, from the origin of his first name to the global environment.

Origin of name

Thank you for joining us today. It is very nice to meet you today.

Prof. Igarashi:

Nice to meet you, too.

First of all, I saw your video on TED.

Have you really been often told that you have a unique name?

Prof. Igarashi:

Yes, since I was a child.

Why did your grandfather give your father a name ending with Chinese character "ko子" (literally meaning 'child' in Japanese)? I hear that your grandfather didn't have a name with that character.

Prof. Igarashi:

There is a shrine called Igarashi Shrine in Niigata Prefecture in northern Japan. The shrine is dedicated to Ikatarashihiko-no-Mikoto, a prince of the 11th Japanese Emperor Suinin in ancient times. The deity's name also ends with "hiko". Similarly, my father's name is pronounced "hiko" in the last part, which I feel is rather common. Despite the pronunciation, however, his name uses the character "ko子", which is uncommon for Japanese boys and common for Japanese girls, and it never failed to make him misunderstood as a girl, which I presume my grandfather also understood. Actually, I don't know the exact reason for his naming like that. The single fact is that my grandfather named my father and uncle with the characters "日子" (hiko in pronunciation), and my father followed him, naming my elder brother and me with the same characters.

Do you think that your father named you and your elder with "日子" just as he was named by his father, your grandfather, because he thought his name had brought him some luck?

Prof. Igarashi:

I agree. I assume that he named us with these characters because his name had brought him more good things than bad ones. Moreover, my elder brother and I also named our sons with "日子". Using the unique name for three successive generations sounds like a family tradition, doesn't it? [Laughing]

Exactly.

Prof. Igarashi:

On the other hand, girls' names using the character "子" had been popular for only a short period from the early 1900s to the 1970s, before which such names were reportedly not considered common for ladies in particular. Even today, these names are considered ladies' names, though not ranked among the most popular names. Tracing the history of names with the character makes me wonder about common sense.

That's interesting. Positive doubt about common sense has something in common with an attitude in science.

Prof. Igarashi:

You're right. As an example, there was a time when Mt. Fuji was not the highest mountain in Japan. Taiwan has two mountains higher than Mt. Fuji. When Japan ruled Taiwan, teachers taught us that one of them called Mt. Yu Sh?n at 3,978 meters above sea level was "Japan's highest mountain." This fact indicates that what we consider common sense contains diverse types of judgement when examined or deliberated on: from what is absolutely common sense to what is now considered common sense, but is actually uncertain. This attitude of doubting what is taken for granted is also essential in science.

Once engaged in research, you will accept this idea rather without difficulty, but it was really shocking to me to know that what is written in textbooks may be overturned when it turns out false.

Prof. Igarashi:

School textbooks were well elaborated on after being prepared based on scientific results at the time, while those results or premises are often overturned in science. Accordingly, what is most probable at this moment is written in current textbooks for schools.

Schooldays

Now that you are a science researcher, did you prefer science to other subjects from a young age?

Prof. Igarashi:

Actually, I liked the Japanese language when I was an elementary school student, or rather liked writing.

I won a prize in a book report competition held by Osaka Prefecture.

Really? Do you also like reading books?

Prof. Igarashi:

Not really, I didn't like reading much. I just loved writing. [Laughing]

Book reports remind me of only bad memories…

Prof. Igarashi:

It does usually. In that sense, I may have been a little different from other children. However, when I entered junior high school, I came to like science. I met a very good science teacher. As part of his class, I participated in an invention competition, and won a prize in the third grade.

Recently, I was awarded the Ichimura Prize in Industry for Distinguished Achievement for my research titled "Solving traffic jam of polysaccharide degrading enzymes toward realization of biorefinery". I remember that I received an invention prize while at school, which was called the Ichimura Prize in Invention for Effort, an equivalent of my recently awarded Ichimura Prize for elementary and junior high school students. Later I learned that I was the first person to win the Ichimura Prizes both for a student and for an adult.

That's marvelous! Do you think other winners of the prize are also active in different fields?

Prof. Igarashi:

That is what I'm curious about, too. Even after winning the prize, I kept pursuing my interest in science and have followed the career path of a scientist without hesitation. [Laughing]

So, what invention won you the prize as a student?

Prof. Igarashi:

The theme was "Cellophane tape dispenser with measured cut." I devised a tape dispenser feeding tape in a predetermined length. After receiving the prize, I saw my idea copied in various fields. [Laughing]

Then the invention triggered you to get into the fun of science, didn't it?

Prof. Igarashi:

Exactly. That is largely due to my encounter with teachers. Among them, the chemistry teacher whom I met in high school was interesting. He allowed me to enjoy chemistry, although I was shocked upon finding chemistry at university so difficult, beyond comparison with that at high school. [Laughing]

You specialized in chemistry at university. How did you enjoy your undergraduate student life then?

Prof. Igarashi:

I never studied. [Laughing] Instead, I played tennis. I joined a tennis club, which was so enthusiastic that we had practiced eight times a week.

Eight times! More than once a day…

Prof. Igarashi:

We had one day off, and two morning practices a week.

You mean you dedicated a couple of years as an undergraduate student to tennis.

Prof. Igarashi:

That's right. I hardly play now, though. By the way, I chose the Faculty of Agriculture because I didn't do well in 1st to 2nd grade before going to the faculty. The faculty was not so popular among applicants, particularly less was the Department of Forest Products where I studied, while agricultural departments still remain unpopular today.

Even today? That's a little surprising because I think that the term biotechnology has become relatively common these days.

Prof. Igarashi:

Slightly better than before, I suppose, but biotechnology appears to be more associated with medicine. What's more, we are at the Department of Forest Products. Forest products seem to students far removed from biotechnology, just as JAXA does from biotechnology.

Certainly, I associated the faculty of agriculture with fields or the agricultural and forestry industry while a student.

Prof. Igarashi:

I see. So, my department was often called things like the loggers' department and other names at that time. I can't deny the naming, however, because we actually had a logging practice program in the course. [Laughing]

I see. [Laughing] Now that I am engaged in life science studies, I sometimes regret that I should have studied at the faculty of agriculture.

Prof. Igarashi:

To tell you the truth, I belatedly realize that I made a good choice.

Research life

You are now active as a researcher (in academia). Have you ever thought of working for a company?

Prof. Igarashi:

I originally thought that working for a company was common. As I was sponsored by a company scholarship when assigned to my laboratory, I thought I would work for the company after graduating from the university. However, the company merged with another one before my graduation. The merger may have resulted in a change in company policy. One of the company's personnel contacted me, saying, "We have decided not to hire researchers. You can work at our company if you don't mind working in jobs other than in research." At that time, I had already begun to find fun in research and intended to continue my research even at the company, so after wavering I decided to go to postgraduate school. Even though knowing that I would hardly get lucky, I asked the company, "Do you have any plans to sponsor postgraduate students with scholarships?" They answered, "We have no plan for a scholarship system for them because we changed our policy to not hire employees for research." It was hardly surprising, but still quite shocking for me.

That is different from what I imagined. I had thought you originally chose to be an academic researcher, as you had mentioned how much you liked invention and science since childhood.

Prof. Igarashi:

The characteristics seen in faculty staff have changed greatly to date since many years ago. I presume that more members have various backgrounds, while some are so-called typical researchers.

What kind of research did you do in graduate school?

Prof. Igarashi:

Exactly the same as at present. Almost all of my publications since I started research are related to ideas, such as extracting energy from cellulosic biomass or basic knowledge for converting cellulosic biomass to useful substances.

Continuing research itself is so difficult. I sincerely admire you even if only for your continued efforts.

Prof. Igarashi:

I think that researchers have their own styles and that I have been lucky in being able to continue my research in my style. I am also thankful for the world's trends that I didn't notice when first starting research. My chosen field of research was very unpopular, and cellulosic biomass research had become increasingly less active when oil and natural gas were yielded at less cost and in larger quantities. While studies in this discipline have been at the mercy of the times as you can see, the terms "sustainable society" and "clean energy" are increasingly common nowadays, and ordinary people are more aware of the impossibility for humans to continue living current lifestyles. Accordingly, the need for this discipline has gradually become more recognized.

I have an impression that you have introduced a variety of the latest experimental methods for clarification, while focusing on consistent research themes.

Prof. Igarashi:

You are right. I am an early adopter and like trying new things. I always ask: "What will this method enable me to do if applied to my research?" The same applies to the space experiment. Once I was consulted about it, I hopefully thought: "I really want to do! I will!"

You need both belief and flexibility. It must take much courage for you to apply an unknown experimental method

Prof. Igarashi:

I assume that the desire to try a new method overweighs any courage needed. Look for a person involved with technology that I find attractive, meet and talk with that person, and then conduct joint research with him or her if we click with each other?this is how I develop my research.

Has your interest in the research themes ever shifted to others?

Prof. Igarashi:

Trying a variety of experimental methods hardly allows the current research itself to become monotonous. If anything, I feel that I am always doing something new because I have conducted research from diverse perspectives.

What is the most impressive event in your life as a researcher?

Prof. Igarashi:

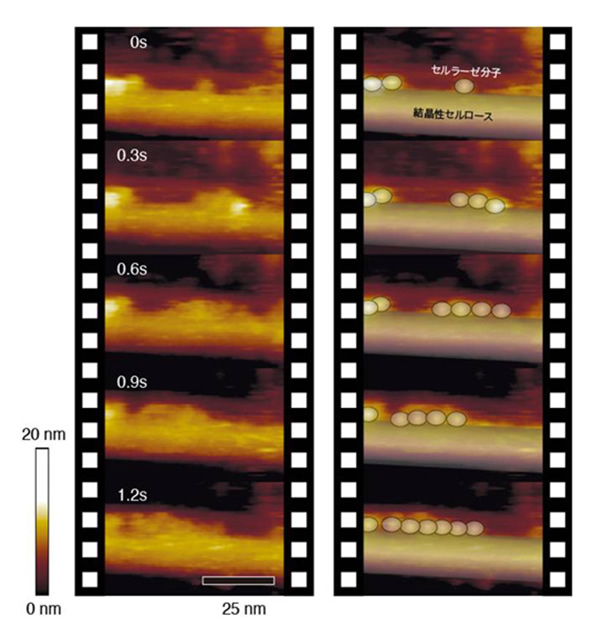

I'm sure it was what I had successfully observed with my own eyes ? cellulase degrading cellulose. The result obtained with a high-speed atomic force microscope was what I had been certain would enable us to enhance our research to top-level science. However, the plan had remained unrealized for more than a decade, without an actual method to be applied. Later, advanced developments in experiment technology helped us achieve the observation, the result of which was published in Science that ranks among the top academic journal about the natural sciences. It was nothing but pure delight for us.

Image captured by the high-speed atomic force microscope. Cellulase moving from right to left on cellulose crystal. As time passes, cellulase causes a "traffic jam." (Credit: The University of Tokyo)

I was also excited upon first seeing your experiment result. Didn't you have any difficulties until obtaining such an amazing result?

Prof. Igarashi:

What I feel is that researchers, particularly in my discipline, tend to shut themselves out from realizing their potential to broaden the horizon. I have often heard researchers saying that their disciplines cannot be science that will influence ordinary people, or that they therefore would never believe in their wildest dreams that their theses could be published in Science or Nature (or other top-ranked academic journals that publish articles about the natural sciences), which focuses on more general and more universally intriguing results. Having worked in the discipline for a long time, I came across such a disappointing situation many times and have also have been personally surrounded by that environment. At the same time, I have also wondered about the closed nature and have doubted if it is really impossible to convey my research, which I enjoy so much. It was under these circumstances that we achieved what we wanted, in order to make our discipline a top-level science, which made me incredibly happy. I never thought of my projects as being shabby or uninteresting, or even wanted to think like that. I think any researcher who sincerely works on his or her research earnestly will inevitably find something interesting in it.

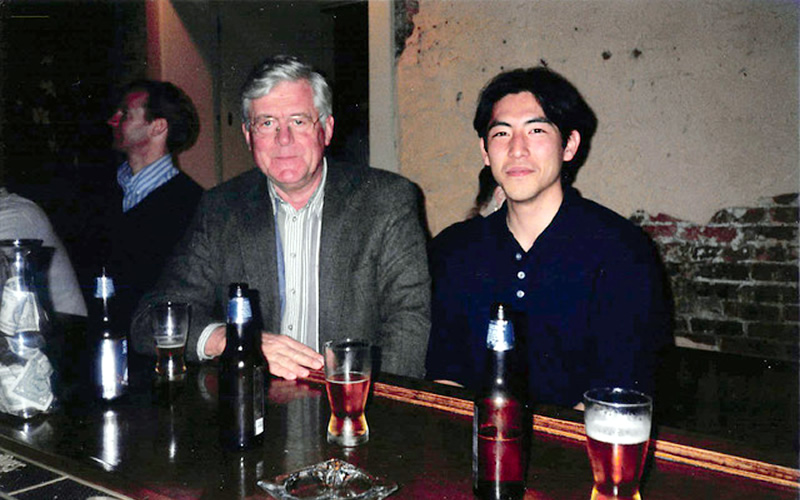

The same applies to my supervisor, Professor Masahiro Samejima (Laboratory of Forest Chemistry, Department of Biomaterial Sciences, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, Faculty of Agriculture, The University of Tokyo), and the late professor Karl-Erik L. Eriksson, a biochemist who was at the University of Georgia and looked after me when I was there as a postgraduate student. They fully enjoy their research. Even in his 70s, Professor Eriksson looked as happy and joyful as a little child whenever he got a new result. Seeing those people may have helped me keep going without losing motivation.

Ms. Tachioka, have you had any experience like some highlight in your research life as Prof. Igarashi mentioned? (Ms. Mikako Tachioka (Doctoral Course Student), Laboratory of Forest Chemistry, Department of Biomaterial Sciences, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo)

Ms. Tachioka:

I succeeded in research which my seniors have long conducted and advanced considerably. At first, I wondered what I could do at that time for research that very intelligent students had earnestly worked on. Continuing the research for about five years, however, even I gradually found something I wanted to say. I thus realized that this is what research is about, and it gave me confidence, although nothing like any particularly big topic.

Now you are steadily walking on the career path as a researcher.

Ms. Tachioka:

At that time, I liked studying but was one of those people who get satisfaction by swallowing whole what is written. My research life allowed me to learn from Professor Igarashi that things do not always go well as described in school textbooks, which I did experience.

Prof. Igarashi:

Just as she said. [Laughing]

It's encouraging to see younger researchers steadily growing up. Do you think Professor Igarashi takes pleasure in conducting an experiment?

Ms. Tachioka:

Yes. Conducting an experiment with him makes me think what I am doing now is really fun and worth doing.

Prof. Igarashi:

You are not made to think it is fun, but it is fun indeed!

Research and education

Do you consider enjoying yourself as a researcher to be most important after all?

Prof. Igarashi:

Exactly. Of course, enjoying yourself requires that you must first make efforts, but what matters is that you are striving in order to enjoy. When checking the data submitted by students, for example, I try hard to find out what part of the result is fun. This is not only for myself, but also for the students. Conducting research at university naturally gives me opportunities to meet young students. While talking with them, I find that many students feel that their experiment or observation of their experiment result is "valueless" only looking at the surface. Actually, if they desperately take another step into valuelessness and pass through it, something interesting awaits them. However, it seems to me that many students return before having a try. My past experience convinced me of it with more certainty. This tip may be true of not only research but also about everything.

Similarly, I think research on which articles are published in Science or Nature may also have the same story: although it didn't look so interesting on the surface at first, researchers had the courage to take one more step and break barriers. It may be the researchers, who found something beyond the barriers, that enabled research to subsequently progress.

In my case, thinking carefully, I find we never know whether this could really happen: this enzyme is interesting, and that one is not. This finding helps me feel better. I now believe that any theme shows us something interesting once we delve into it.

These days, it has become more important for researchers to make efforts in conveying the interests of research to ordinary people.

Prof. Igarashi:

I agree. On this point, my love of the Japanese language in my childhood does help me even now. Besides, I wrote essays to improve my writing skills. These helped me to convey things without difficulty. However, the younger generation is poor at conveying what they want to. They should consciously polish their skills because making an appeal is important not only in research but also in everything.

Faculty staff serve not only as researchers but also as educators.

Prof. Igarashi:

I think that I am not cut out to be an educator. Nevertheless, I often taught students for the first several years after becoming a faculty member. However, one day I realized the importance of teaching and found it difficult to continue in the same way, while thinking that showing students what I am doing, or forerunning by myself would be more effective for the students. These days, I think that students only see me conducting research earnestly and pleasantly. That's all I can do.

As I grow older, students coming to university remain the same age, which means the age gap is getting larger. When I started working at the university, I was able to talk with them from the same viewpoint because I was only slightly older. Now, it is difficult for me to talk the same way, and students now view me differently than before. Partly due to this situation, I have actually begun to gradually change my way of educating students. Currently, I also have a position in Finland (as visiting professor at VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland Ltd.). One of the reasons I took the position was that I wanted to show students that there are possible options in walking on such a path.

Space

What are you most interested in now?

Prof. Igarashi:

I have long been interested in living things that live on trees and plants, which are fungi including mushrooms. However, given the limited experimental methods available for fungi and the extreme difficulty in conducting research that targets living things, I engaged in research focused on "an enzyme as an actual body that degrades trees and plants" around when I entered the doctoral course. Aren't you curious about what made fungi (the so-called "cleaner in forests") come to live on trees and plants, and what enabled to evolve into a species that lives on what other living things do not eat? And the metabolizing of fungi by trees and plants also contributes to conservation and restoration of the global environment. This is actually quite a spectacular story.

Fungi, plain at first glance, can be a hidden key role player in the context of the global environment and the life of living things.

Prof. Igarashi:

Certainly. Humans, trees, and plants that stand out may appear to be representative of the living things on Earth, whereas we assume that mushrooms and fungi actually play a more important role.

So, you would not consider it strange if aliens viewed Earth as a planet of fungi when seen from space, as people have diverse views.

Prof. Igarashi:

Yes. I think so.

What do you do when you are away from research?

Prof. Igarashi:

Nothing in particular, I'd say I make plastic Gundam models. It may be a reaction to what I could not do in my childhood. Now that I have grown up and can afford plastic models and related tools, I bought an air brush with my money as I wanted…

That is sort of buying with your own money a large amount of the toys that you didn't have in your childhood? [Laughing]

Prof. Igarashi:

That's right. I only make one or two plastic models a year because I don't have much free time, so there are plastic models remaining to be assembled, standing in line at my home.

Gundam is set in space.

Prof. Igarashi:

I remember recently purchasing Gachapon Japanese capsule toys at JAXA as well. I buy one at JAXA whenever I pass through its nearest station at Shin-Ochanomizu. As a result, I now have almost the full collection of capsule toys.

Thank you very much. [Laughing] Were you interested in space when you were a child?

Prof. Igarashi:

Yes, I was. I had an illustrated reference book of space that showed the Saturn rocket developed and operated by NASA, which launched as many as 12 astronauts in total to the moon during the Apollo program), and other things. When I saw that image, I wanted to go into space someday. Even though I unfortunately did not achieve my wish, I still want to go even now. When I was very young, such anime set in space, such as the Space Battleship Yamato and Gundam, were popular and children thus had more opportunities to feel closer with the universe. Compared with those days, how do children at present feel about space?

Children may be dreaming less about space these days.

Prof. Igarashi:

I think so, too. In other words, space has become a more realistic and familiar place rather than a place that people dream about. What I realized after actually participating in space experiments was that there used to be a contrasting structure like the earth or space, or other than space. Today, we can enjoy space in more subdivided ways. For example, instead of just saying "space," we could describe it as weightlessness and no air. This suggests how to enjoy space as a representative specific environment. In the past, we felt vaguely romantic about space, but did not think about it in a subdivided way.

More findings may have allowed people to enjoy space in their own enthusiastic way. In other words, ordinary people have come to have their own ways to enjoy space, just as experts enjoy their research in their own respective disciplines. And this trend is not only about space. People can now access information of personal interest on the Internet at any time.

In the context of a specific environment, I am as much interested in the deep sea as in space.

Prof. Igarashi:

Really? So am I. To tell you the truth, Ms. Tachioka is scheduled to start working at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC) this coming April. The deep sea is an interesting place where you can clarify the existence of living things at unexpected levels, and thus break your own barriers about thinking that living things would not survive here.

Ms. Tachioka:

Being influenced by Professor Igarashi, I have become interested in the deep sea. Space and the deep sea look distant, but have something in common in the context of extreme environments.

I see. Could you tell me when you find something interesting?

Ms. Tachioka:

Let's conduct joint research then!

To young people

I am often asked this question: Is there anything that I should do to be a researcher while at university?

Prof. Igarashi:

What is it? Not studying, certainly. [Laughing]

We may receive complaints from many people if we say so.

Prof. Igarashi:

You are right. Certainly, it is good to study. However, I feel sorry for children who spend so much time studying. I think of the distress given children by an environment that demands almost all of their time for studying, including preparations for entrance exams, without any time to do something else, except those who love that kind of environment. Present-day children look really busy, don't they? Thus, I proposed to my son the possibility of not taking university entrance exams, and instead going to an institute of technology. I recommend institutes of technology as a good choice for students who have clarified what they want to do to some extent. They can accumulate practical experience and easily understand the need to learn. In addition, they can transfer to a university after graduation. It is an effective option for students to secure their own time while still young.

I also wish I had clearly known about the institute of technology system.

Prof. Igarashi:

I understand. And when hunting for jobs, students usually just choose one of the paths presented to them, even though they think they need to decide their own paths. It may be important to present them with many more options.

What is bioeconomy?

I saw your article about bioeconomy.

I honestly didn't know the term before reading your very informative article.

Prof. Igarashi:

Thank you very much.

In your article you mentioned, "it is important to know correctly and accept the definition of the term bioeconomy," and "many companies, organizations and people, which seem to develop activities covered by bioeconomy in some way, should ensure that their activities are properly associated with bioeconomy." What do you think is necessary for Japan, which lags behind other countries such as those in Europe?

Prof. Igarashi:

To clarify the answer, I think Japan lacks abundance. When I went to Nordic countries, I realized one thing: only wealthy people or those who pursue wealth can think about their link with bioeconomy. Sustainability and a sustainable society are increasingly common now. Currently, people overuse energy. Furthermore, the energy of the earth is not well balanced. So many organizations tend to include the terms in their action policy or slogan, which is not a bad thing. At the same time, they may use such terms as an excuse. The present situation cannot be handled only by the efforts of part of an organization, but demands everyone's awareness, which falls short due to the current immature consciousness of Japan's beauty and the importance of pursuing it. This consciousness includes how people should work. For example, a Finnish person told me if Japanese society consciously tries to work in pace with women, people would not work like this. Finnish people work about one-third less than Japanese people, and earn about 1.5 times more. Their unit price is more than double that of Japanese people. This is only an example of such an environment that allows people to spend time and money on bioeconomy, sustainability, and other goals. Even when a product is expensive, people would buy it if it complies with bioeconomy. Of course, what I mentioned is rather an extreme case, and Japan apparently lacks in abundance in a financial sense and other ways as well. It is rather too much bent-on. We feel neither leeway, latitude nor generosity.

This is very difficult.

Prof. Igarashi:

It is. But things begin with knowing and having consciousness. After starting the space experiment, I was reassured that it is literally a matter of Spaceship Earth. Properly maintaining life within the International Space Station (ISS), a specific isolated environment, is a model or miniaturized version of maintaining the earth. In the environment, people should address issues like how to save and reproduce water, and how to operate the life support environment.

Yes, definitely. If water falls short onboard the ISS, there are some possible measures, such as bringing water from the earth and returning to the earth in case of an emergency. However, the circumstances seem to be tougher on the earth where we have no place to escape.

Prof. Igarashi:

I agree. Therefore, not based on the dualism of the earth or space, but on an idea of coexistence of the earth and space, we think of the earth through the ISS in space as previously mentioned and cannot help but work for the global environment, being more conscious of what ISS teaches us. In that sense, the ISS plays an important role in our consideration of bioeconomy.

Post-interview comments

The interview demonstrated the magnificent scale of Professor Igarashi, a scientist and dedicated writer, who deliberates on the global environment, while elaborating on research on fungi and mushrooms.

Saying that having no interest is useless is really encouraging, and his explanations tell us many things.

We look forward to the future activities of Prof. Igarashi! Thank you very much.